I Could Be Way Off Here

ODIN'S AVIARY ~ a home for wayward thoughts & memories

Oh. Oh-ho. Oh-ho-ho.

Yeah. I'm going to do it. Why? Same reason as I like to route (root? rewt?) for the team that has the least chance of winning. I love the downtrodden.

In my last entry, I admitted it would be tantamount to readership suicide to post an entry on prop comedy. Since then, I haven't stopped thinking about doing just that. I also, in that entry, said murderous clowns are an entry unto themselves, but I thought we could all use a break from my current clown obsession.

I have a friend whose email address used to begin with "killgallagher@". (Hi Dave [Youmans].) I always thought this was a bit excessive, though memorable enough. (I can hardly throw stones; for years and year my email was "sukeu@", and for years and years people pronounced it as various forms of "sucky" [it's soo-kay-yoo {I digress}].) Yet there I found myself, Gallagher-bashing with righteous vehemence in my last entry. It reminded me of Friend Kate's feelings about trade-marking. She finds it unjust that anyone can claim a name, and that it inevitably infringes and goes on to claim ownership of the idea behind the name, at least in people's minds. I resent, abhor and resent some more this so-called "Gallagher" because he's taken a perfectly legitimate -- nay, occasionally sublime -- form of theatre and made himself and his simple, gratuitous form of it synonamous.

Same goes for Carrot Top.

My feeling is that, putting it very generally, prop comedy these days suffers from a pursuit of the punchline. Take, for example, coitus. Or, in the common parlance, "bumpin' uglies." Oh sure, you can simply chase the payoff. It's a short trip with an obvious reward, and somehow sometimes seems more guaranteed, if such a thing can be in life. But is it really what it's all about? Haven't we all had better experiences when we take our time, appreciate the moments and -- dare we say it -- the relationship involved? Even in a single night's adventure, there is a relationship. Ignore it at your own peril.

I admit: The comparison is a little unnecessary. I'm just a sucker for a good simile. My point is, prop comedy suffers from short attention span (of the performer as much as the audience) and a lack of development. A prop may occasionally be good for a one-liner sort of joke, and in this instance we term it a "sight gag" mor eoften than not. But real, good prop comedy, to my taste, is best explored in terms of relationships.

And, of course, relationships change over time. These are not categories to singly adhere to, but forms to specify something more organic and unpredictable.

It may seem silly to some to create these sorts of relationships with objects. It occasionally seems that way to me, too, until I observe that these relationships already exist off-stage. Have you never seen a coworker assault his or her unruly stapler, or an older gentleman who caresses his cane as he sits? Theatre, in the all-encompassing sense, comes down to people coming together to have a good natter, and other people coming to watch it happen. Good prop comedy is not an exagerration of our relationships with objects, but an exploration of our relationship to our environment. Good prop comedy is funny, true, and by different turns often frightening or melancholy. It should be fascinating.

And we shouldn't have to explode a watermellon to do it.

has a great story about a teacher she had at Dell'Arte. The students there had to present an original, solo clown piece at least every week, and this teacher had a habit of viewing these pieces with a bucket of tennis balls by his side. If, in his opinion, the scene was not playing up to snuff, he would begin to peg these tennis balls at the performer, all the while shouting, "NOT...FUNNY...!" This became something of an inside joke as we worked on various

shows. That, and our favorite, gentle way of telling someone their idea sucked: "Hm. That might be a great idea for

next year's

show...."

(if I haven't completely alienated him with my response [and if my atrocious XBox playing hasn't alienated him, how could a caustic response to his opinions?]) posted a comment on my last entry regarding clowning (see

) that suggested that clowns are not funny, and that the reason for this is that they overwhelm, and turn a cathartic fear response into more of a Godzilla!-Run-for-your-meager-lives! response. I guess my entry didn't clear up any of Adam's feelings in this matter. Or, at least, I failed to extricate the word "clown" from the American stigma for it. To me, you see, "clown" is not a fair word to use to describe the circus or birthday clown. Hell: I don't even like "circus clown," because the word "circus" means a whole lot of different things, too, once you step outside the three rings of Barnum & Bailey.

So before I continue, let me break some things down. I see the stereotypical western clown as a kind of collage of comic traditions. (Note: THIS IS NOT A SCHOLARLY TEXT. For heaven's sakes, don't cite me as any kind of authority. It's been a decade since I took any kind of history class, and I didn't start taking an interest in clowning until about five years ago.) As I stated so elegantly, and ineffectively, on the 28th, the "birthday clown" has become a kind of grotesque take on some time-worn and valid comic traditions:

The past week has for me been very clowny. I continue to read my Buster book. I've had two auditions (auditions themselves being very similar to the torment a clown experiences moment-to-moment [at least, my clown does]), and one of them required an original movement piece. To top it all off, I had a conference with the Exploding Yurts -- my little creative-encouragement group with a strange name -- regarding the draft of a screenplay for a clown film I'm writing. (Because struggling to become a renowned theatre actor just isn't frustrating enough.) I don't know why I'm turning to the clown in me so much these days. I suppose it could have something to do with working on that whole "what kind of work is MY kind of work" question I began asking somemonthsback.

And it seems I'm getting an answer. Or three.

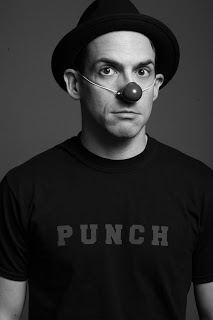

Photo by Jimmi Kilduff.

I heard recently (can't recall where) that a fear of clowns was the universal fear of all children. I know some adults who would postulate that children ain't the half of it. Clown fear, or

coulrophobia

, is prevalent. Of that there can be no doubt. Check some articles, my fine, feathered readers: and a-

, and a-

, and a-

. I hardly feel a need to provide references for this phobia, however. It seems to be universally understood that clowns are, under the right, or wrong or, for some, any circumstances, scary.

backs this up. He doesn't like clowns, either (though apparently the Puck from Neil Gaiman's Sandman he's just hunky-dorry with), and one of his best friends is a clown. It's tearing our nation apart! It's brother against brother! Cats and dogs, living together; mass hysteria!

And that is what I think the fear of clowns comes down to. Someone, please, tell me if I've got it all backward. I'd love further insight into coulrophobia. (And while you're at it, please break down the etymology of that word, too.) To me, who only fears the certain, intentionally scary clown, it comes down to anarchy. People simply don't know what a clown will do next, and on top of that, clowns are the ultimate breakers of the fourth wall, or the audience-performer separation. We can't exist without you, audience. If a clown gets his foot lodged in a trashcan, then stumbles around until accidentally setting himself on fire, and no one's around to hear the screams of agony, did the clown really get his foot lodged in a trashcan and stumble around until accidentally setting himself aflame? The sad answer is: No, my dear audience. No.

I love clown work. I was introduced to it as a performer by a fellow clown,

. Friend Grey graduated from the

, is a member in good standing of

, and directed our only full-length clown production to date:

Silent Lives

. I think it's safe to say that Grey feels she learned a lot from clowning--the which she does in the general

/red-nose style--and applies those lessons to the rest of her life. I was very cautious to enter that world for quite a while. Rather like my few flirtations with attempting dance, I would find myself feeling lost in the work, a stranger in a strange land, and quickly become discouraged. Add to that all the aspects of clowning that actors are trained

not

to do, such as acknowledging the audience or drastically modifying one's behavior on stage in response to them, and you have yourself a pretty scary little world to enter . . . even without the intimidation of how personal clown work is. The idea is that one's clown is unique to one's self, thriving on our unexpressed emotions, and that the more difficult a time the clown is having, the funnier it is to the audience.

Taken from that perspective, I wonder if persons suffering from coulrophobia might not start to feel some sympathy for the clowns they meet.

It's unfortunate that, in our community at large (I'm speaking here of the U.S. of America, people), a "clown" has the stigma that it does. Google images of "clown" and (as of the date of this writing) you get that whole "birthday-clown" package, replete with elaborate face paint, grotesque colors and ginormous shoes. You also get Google suggesting you try searching for "

scary

clowns

." The allegory here is very nearly self-evident. I don't know a lot about how the birthday clown(TM) became the prototype clown for us. I can assume influences from what I know of clown history, but that's just what they'd be: assumptions. I do go so far as to suggest, however, that the birthday clown is the result of a certain competitive and/or capitalistic philosophy we tend to adopt, knowingly or no. Drive anything to a certain point of extremes, and it will become grotesque.

These things do not a clown make. We've got clowns we love (or hate) unabashedly, without fear, surrounding us in our culture. Certainly

two of the greatest silent-film comedians

were clowns (I'm not sure I'd classify Harold Lloyd as one; I see him as beginning the swing toward more naturalistic comedy), and possibly the birthday clown has borrowed from their pedestrian wardrobe.

is a clown, and I don't mean that in the derogatory sense. I mean that he is an iconic comedian, heavily dependent upon his audience, and who is developed out of the particular personality of a performer. The fact that he is also a scripted telelvision "host," more verbally motivated than driven by pratfall, is simply an adaptation to the time, and has evolved from other, more Western traditions of clowning. I believe Simon Cowell may be a clown, too. If he really behaves the way he does on

American Idol

at all times in his life, well, then he's not, and I pity him.

The funny thing about clowns (ha-ha), is that we are essentially children. I've spoken to a lot of people with theories from all sorts of places about why this fear of clowns. My sister recently insisted that the "traditional" clown face-painting taps into a primal fear of death, that children see a white face and know instinctively that it means a dead person. Could be. Lots of articles suggest that clowns are chaos-makers, and most mythologies contain some such figure, which is often associated with animalistic behavior. A fear of clowns, then, is a survival instinct, a defensive reaction to something outside one's community that has found its way in. (Never mind that many Native Americans figured this clown figure--Raven--for having created the world.) I can dig it. Me, though: I think people are threatened by the anarchy of a person behaving child-like. That is, in ignorance of "the rules."

As I grow older and (ever-so-slowly) more mature, I value what the clown has to teach me more and more. The clown takes nothing for granted. The clown makes mistakes regularly, and makes them with absolute commitment, and sometimes they even work out for him or her, in which case he or she never comes to view it as a mistake. The clown sees purpose in everything, understanding in nothing. The clown is selfish in its needs, yet absolutely dependent on the love of others. The clown, in short, makes me feel a little less an "adult, " and a little more human.

Which, I admit, can be scary.

Plus one I do believe in: God.

What inspired this rant of rejection, especially from one whose history is so steeped in a faith of universal acceptance? I have been noticing and reading a lot lately--or so it seems to me--about Atheism as a movement. I do not oppose this movement. On the contrary, I think Atheists have been rather oppressed in our global culture, and I don't like anyone to be oppressed (REpressed, sometimes...) and so, say "Bully!" to the outspoken Atheists. I worry, however, over the way so many of them with the benefit of the public ear are immediately resorting to the stampeding debate tactics of those further into a life of faith that they so oppose. It's natural, when your beliefs are shaped by what you don't believe, to oppose another view, and nascent societies (such as openly atheistic groups in America) are bound to overstate their claim when they finally get a voice. So maybe I've nothing to worry about. Maybe them thar' Atheists will never become quite as fascist as to start bombing cathedrals and synagogues.

I believe in God, and it's important you know that if you're going to know me. I know there's no empirical evidence for the big G. I know lots of people think they have lots of conclusive evidence that God can't exist. I don't disagree with such people on any particular point, and actually tend to agree with the "facts," as scientists understand them. I even agree with Lennon, "Imagine," and think the world would be a much more peaceful place without religion. So why do I continue to believe in God? Is it just because I'm a minister's son? Is it stubborn wishful thinking, or deep-seeded superstition? Perhaps it's just playing it safe.

It's that I believe in something greater than all we can perceive. This "greater" thing is pervasive, interconnects us and has more meaningful significance than forces like gravity and magnetism (hell: it may be the source of all force[s]). It's not important to me that the greatness, which I'll go ahead and call God from here on out, created us, or nurtures us, or even has any personally conceivable relationship to us. What is important, to my mind and heart, is that the belief in God keep us from turning completely into self-important little gits, hell-bent on destroying one another and our celestial terrarium. I feel most in a spirit of God when I am grateful for life, all of it, and I can do that without seeing God as a man or regarding a book as gooder than most (the gooderest book). So rock on, Atheists. Get heard. I'm all for it. I hope you do some good in the world.

Me, though: I'm a believer.