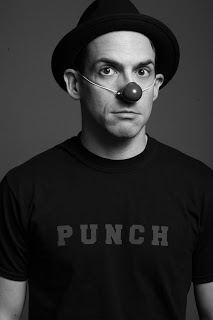

Last night was my solo clown debut.

Well, not precisely. I have done a number of solo clown performances in my time. Last night merely marked the first time I did so on an actual stage. Up until this event, my solo clowning was largely busked and/or filmic. In fact, I volunteered for the festival hosting clown and puppet events because I wanted to have a good deadline for adapting this particular solo routine to a stage. Plus I was desperate for work, at the time. Naturally, I completely ignored this opportunity to

work

on the piece, and found myself panicky all day yesterday, contemplating exactly what I was going to do up there that night.

It went okay, rife with the peaks and valleys I might have expected from a debut work in a nurturing yet unexpectedly intimate environment of strangers. I didn't, of course, expect these variances in my experience. No, I find that when contemplating performance I'm usually surprised by the comparisons between my expectations and the experience. I expect complete victory or total failure; the median is difficult to imagine, the variable completely confounding. This is possibly because the more intense the stage fright or adrenaline, the more apt I am to think in absolutes. Or, it could be that the (utterly erroneous) stereotypical mentality of a struggling actor has infected my imagination deeper than I, er, imagined. In other words, the idea that

just one big hit

could change everything for me may contribute to the absolutes I contemplate. Either way, the product was, in some respect, just like every other. Some things went over great. Others, not so much.

I have yet to attempt any kind of monodrama, or extended solo performance as such. Outside of a few scattered soliloquies, I'm always acting with other performers. Last night I found a popular axiom to be doubly true and especially so for live silent comedy: When you lose the audience, there's no one to turn to but yourself.

Not so backstage. The worlds of circus, clown and other "gig acts" is a small one anywhere, I'd imagine. That goes double for New York, where you're just as likely to run into your babysitter from age 5 as you are to never see current friends who live just two neighborhoods over. I happened to get ensnared in this show's clutches through an email sent out by one

requesting acts. I know Jenny through

Friend Dave (Berent [nee Gochfeld])

, whom I know through Friend Heather (whom I know from having worked with her in

), but I also knew Dave as the more male half of

, and vaudeville act he did with

. Dave and Jenny have also done shows with

(which is the home of Zuppa del Giorno). I did one of those with Dave, but not Jenny. BUT, I did do

with Jenny's mom, Emily Mitchell, long before I ever met Jenny herself. And finally, who was MCing last night, but the very same clown act,

, that was recently recommended to me by the good and fine people at

, whom I met through working with

(which is also where I met Rachel).

It would seem, after this assault of name-dropping and six-degrees-of-network-makin', that I had all the world backing me up as I prepared for my show. Didn't feel that way, though. Felt very, very alone. Each performers was doing his or her own thing, for the most part, and I was in an advanced state of freak-out. It reminded me of the intense stage fright I felt just before the first show of

, Zuppa's first production. I stood backstage, the first to enter for that show, and suddenly realized, "I have no script. I HAVE NO SCRIPT! It's just

ME

out there!" I did all I could to dispel it, and I actually owe a debt of gratitude to one half of

Bambouk

,

, who stood in front of me and asked, "So, could you use some distracting conversation, or are you better staying in the zone?" Thankfully I had the presence of mind to opt for conversation, and it made for smoother passage into the time spent along backstage.

The trouble in adapting the piece to the stage was in taking some of the fun of its original venue(s) -- places where people are relaxing and not necessarily expecting spontaneous fun -- and translating that into a stage setting, with an audience that had

no choice

but to pay attention. This is a powerfully appealing aspect: choice. It may go a long way toward explaining the historically recent success of cinema over live theatre, in fact. Theatre, in the conventional sense, is a gamble. A movie costs little (comparatively speaking) and can be voluntarily escaped in any of its forms. Walking into a theatre, you know very little about what to expect, and can get subjected to something confusing, unappealing, or just plain ill-executed. And there seems to be no escape. The space I was performing in last night had the advantage of being intimate, with very little audience/performer separation, but that was just about its only similarity to the piazzas I was used to doing the piece in.

What I did to adapt it was very much shaped by having to create an entrance. In the square, you just start acting doofy and see what grabs people, then mold your performance based on feedback and a skeleton. In the theatre, you need to put them at ease, to apply balm to their sense of disorientation at the beginning of any new piece. In public, you grab them, and they tell you where to go next. In the theatre, you have their attention, and then you have to justify it. (Speaking in generalities here, of course; much overlap between the venues.) Needing to create an entrance helped shape my given circumstances. Whereas previously the act was based on the idea of the character as a quasi-homeless, drunk reveler who interrupts a party, last night's incarnation was an awkward fellow

escaping

a party into the kitchen. This allowed for a less invasive characterization at first, and my hope was to put the audience a bit more at ease. Also, whereas previous incarnations took place amongst relaxed (often inebriated) party-goers, this crowd, at a relatively early show in a theatre, seemed to me more likely to be at the energy of such kitchen-clingers. It also allowed for my using a song I have longed longed to use in a show; it closed with the irascibly awkward "

You'll Always Find Me In the Kitchen at Parties

," by

.

And it worked fairly well. I would say, all factors considered, I had the audience pretty well on my side throughout. They did best with bits in which I suffered and they weren't threatened. (This would seem natural enough, save for experiences I've had in which the only way you could begin to entertain certain audiences was to mix things up with them.) Keeping things simple, singular, and taking one's time is essential in clown work. The piece suffered the most at times when I got carried away with my energy, racing the audience and only pouring on more fuel if I felt myself losing them.

The scenario is that Lloyd Schlemiel (my noseless [or silent-filmic] clown character) is trying to quietly escape a party. He backs into the kitchen, all the while munching on Cheetos(

) from an orange bowl. Once he's cleared the doorway, he closes it, and the sounds of the party fade out. He breathes a sigh of relief, and raises another Cheeto to his mouth when he suddenly notices the audience. The Cheeto snaps in his hand. He races for the door again, but is too scared to return to the party, so turns to the audience and makes due. From there it proceeds along fairly typical Lecoq lines, with dabblings of silent-film comics thrown in here and there. He adjusts his clothing, thinking the audience will better approve of him. He decides he doesn't like his hat, and trades it for the "bowl" he was snacking from, which proves to be a mistake. The rest of the sequence involves his trying to escape this hat, which just won't leave him be. He tosses it away, and it returns to him. It clings to his head, despite acrobatic endeavors to remove it, and obscures his vision. He finally frees himself from it, but it's changed him into an extrovert. He performs a striptease (only down to undies, mind), puts the hat back on and rejoins the party.

It needs work, even in verbal explanation, but the performance was a tremendous jump forward for me in making discoveries about it. My hope is to break it out in Italy a bit, and play with it there. We can only pray that they sell Cheetos there. Hell: They end in an "o." They probably are Italian.